Erie has experienced a quiet summer without new drilling operations. I have been living with the hope that because of the precipitous fall in oil and gas market values, that it will not be economically feasible for Encana to return to Erie in the near future. Yet it seems our freedom from new drilling and fracking may be short-lived. Encana recently re-submitted its application to drill at the Pratt site, and there is a meeting on Wednesday (tomorrow) about another proposed drilling site in Erie: Morgan Hill.

Once again I am on edge, wondering how another round of drilling/fracking operations will play out.

I also continue to be amazed at how we as a society fail to learn from our past. Mining and drilling operations cause pollution. Yet people argue over the extent of that pollution and the subsequent environmental impact. Big spills make the headlines. Small spills do not. We ignore ongoing environmental contamination when the overwhelming perception is that the contamination is normal.

Take for instance the spill from the Gold King Mine near Silverton, Colorado that occurred a little over 2 weeks ago. There are many mines in that region that are slowly leaching contaminants into the nearby groundwater. (The Colorado Geological Survey reports that there are approximately 23,000 abandoned mines across our state). The EPA has been working on clean-up projects, first targeting mines that are the biggest problems. However, in the process of initiating the clean-up effort at Gold King, workers breached the soil dam that was holding back contaminated wastewater. Three million gallons of wastewater (containing lead, arsenic, cadmium, and other heavy metals) flowed into Cement Creek and on to the Animas River and beyond. Many people expressed frustration with the EPA for allowing this to happen. Yet I think we need to remember that the EPA did not create this mine; they were tasked with clean-up in the aftermath of mining operations.

To read more about why sub-surface mining results in water accumulation within active and abandoned mines, read about Acid Mine Drainage.

Until I did some research, I assumed that the Gold King Mine is an abandoned mine, i.e. without an owner. But that assumption is wrong. The owner of the Gold King Mine, Todd Hennis, blames another mining company, Kinross Gold of Canada, for the large volume of wastewater that has accumulated within the Gold King Mine. His claim is that when Kinross Gold plugged a portion of one of its mines, that action pushed increased wastewater into other nearby mines including the Gold King Mine. Todd Hennis, who assumed ownership of Gold King Mine via foreclosure when the original owners went bankrupt, believes that he bears no responsibility in the clean-up effort. Furthermore, he blames another company for the high level of wastewater in his mine. So in the end, despite the fact that there is a mine owner and potentially another company that should be contributing to the clean-up effort, there is simply a lot of passing of the buck. As a result, we the American people are left with responsibility for clean-up years after the mine ceased operations. We rely on the EPA to do this kind of work for us, and then we denounce the EPA when something goes terribly wrong with the clean-up effort. Why do we not hold the mining companies accountable? The simple truth is that the people who should shoulder the majority of the blame in this environmental quagmire are no longer alive.

Well before the release of the wastewater that turned the Animas River into an opaque orange color, my husband and I made plans to hike in the Silverton/Ouray area the weekend of August 15. Although our hiking did not take us near the Animas River or Cement Creek, we did spot a river that was orange. While hiking up Bear Creek Trail (toward the abandoned Bear Creek Mine) just outside of Ouray, we identified orange water southwest of us. At the same time, we passed an older gentlemen on the trail, and I asked him if that was Cement Creek. He said, “No, that’s the Uncompahgre River. It’s always that color.” “Great,” I thought. “That cannot be healthy.” Later, while driving toward Silverton, we had better views of the Uncompahgre — and of the orange colored silt that coats the rocks along its shores. Later I compared my photos to the ones I found when Google searching “acid mine drainage.” The Uncompahgre River has the classic appearance of a river suffering from acid mine drainage. This is “normal.”

The EPA estimates that the cost to clean up mines nationwide (excluding coal mines) ranges from $20 billion to $54 billion. In hindsight, we should have had more regulations requiring mining companies to adhere to stringent clean-up practices when operations ended. Yet at the time the mines were developed, mining was driving the economy and creating boom towns. No one wanted to worry about the future — they were only concerned about economic success in the present.

This prioritization of short-term economic gain serves industry well. And industry members (whether they are mining companies, oil/gas companies, etc.) are quick to point out that the public uses the metals and energy that they provide. Yet I still find a price tag of $20 to $54 billion hard to swallow — especially considering the financial gain that the companies responsible for the contamination enjoyed. Furthermore this price tag does not even take into account the cost of the health impacts that may stem from unrecognized contamination.

The Navajo people on a reservation in northeastern Arizona know all too well the health impacts of contamination. For decades they have lived with uranium exposure and massive contamination from uranium mining. For a quick summary of this horrifying story, check out this NPR piece: Yellow Gold: An American Story of a Poisoned Land and a People Betrayed. The estimated cost of the clean-up exceeds $130 million, which means that the process will be slow. For more information, read Uranium Mine Clean Up on Navajo Reservation Could Take 100 Years.

Now that the Navajo people know not to drink (or use for any purpose) the well water on their land, clean and safe water is in short supply. Approximately 40% of the people who live on the reservation do not have running water. They have to make the water they store in barrels last a month or more. Forced to become experts in water conservation, some are able to live off of 7 gallons of water per day (compared to the 100 gallons per day the average American uses). The CBS Sunday Morning Show recently shared this story and profiled a Navajo woman named Darlene Arviso, dubbed “the water lady.” Darlene uses a large truck to deliver water to people on the reservation, as many would otherwise have to drive 100 miles to access water on their own, and few have cars. CBS’s crew showed the remarkable ways in which people on the reservation conserve water. In one instance, they demonstrated how several people may share the same tub of water to take turns washing their hair.

Water is life giving, and we literally cannot survive without it. Yet despite the shortages we frequently face in the West, we fall short when it comes to treating clean water as a priority. We recognize that once contaminated, water should be cleaned. However we fail to recognize that it would be far more cost effective to prevent the contamination in the first place.

Residents who lived in Erie more than 30 years ago talk about how no one drank the well water because it was so contaminated. Today, Erie does not have its own source of water. Instead, Erie purchases water through the Colorado Big Thompson project, which is delivered to Carter Lake in Berthoud. From there, it travels via pipeline directly to our water treatment facility or to our reservoirs for storage. Apparently our water treatment facility does such a good job of removing contaminants and odd-tasting elements that we have “award winning” water: Erie’s drinking water drenched in a cascade of praise. And while I am very happy that our water passes rigorous testing standards, I do not think this gives us license to say that the oil and gas drilling activities in Erie pose no risk to our groundwater. For while Erie has widely publicized it’s recent citizen survey which found that 90% of citizens rate Erie as a good or excellent place to live, and Money magazine ranked Erie #13 of the 50 best small towns in America, a recent spill from one of Encana’s produced water tanks within the agricultural edge of Erie failed to receive any news coverage. In fact, I learned of it on Facebook.

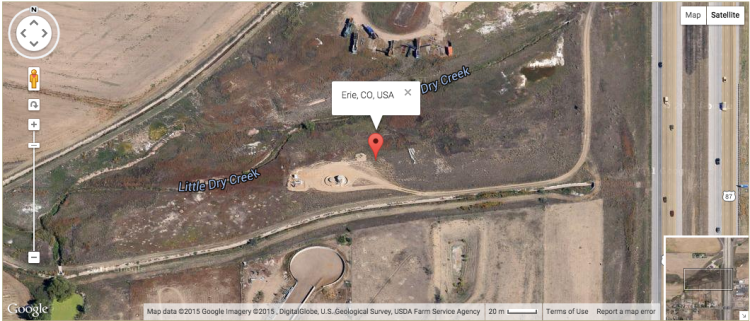

A COGCC document dated 7/2/2015 provides details of a spill from a “produced water tank” near Weld County Road 6 and I-25. Tests of the groundwater near the site of the leak found benzene, toluene, and xylenes at levels that exceed regulatory limits. Soil sample analysis was still pending at the time of the report. Based upon the latitude and longitude in the report, I found an image of the area on Google Earth:

Note the proximity to Little Dry Creek, which flows into the South Platte River. While I have no way of knowing whether any contamination reached the creek, this illustrates the point that water is vulnerable to contamination.

From the COGCC document, I cannot tell how frequently that produced water tank was being inspected prior to this incident. How long had the tank been leaking when the spill was discovered? Or did a spill occur as workers were doing something to it? These are the types of questions I rely on reporters to ask. But this incident flew below the radar and did not make the news.

Sure, maybe this is an isolated incident, and here I am harping on one “little” blunder by Encana. Shame on me. But I long for the day when we treat water as the precious commodity that it is — when we value it before we get to the point that it’s scarcity forces us to behave differently. Unfortunately, we just don’t heed the warnings of our past mistakes.

Nice piece. I’m a fractivist from LA. We will beat this thing eventually!

LikeLike